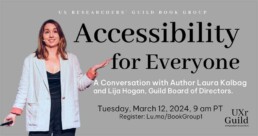

Accessibility for Everyone:

A Conversation with Author Laura Kalbag

with Lija Hogan, Board of Directors, UX Researchers’ Guild

This is an abridgment; view the full video presentation here.

With the launch of WCAG 2.2 in late 2023 and an increased focus on supporting vulnerable populations, many organizations have been actively working to ensure accessibility to digital experiences and products that enable everyone to navigate the world successfully.

Laura Kalbag’s book, “Accessibility for Everyone,” is a premier resource for navigating this ever-changing landscape. In the UX Researchers’ Guild’s first Book Group, Laura and Guild board member Lija Hogan shared their insights and knowledge on this timely topic.

Why Accessibility Matters

Laura considers herself fortunate that she was able to learn about accessibility more than a decade ago, as she learned about how to write code and design for the Internet.

Much of her awareness of the need for accessibility, however, came from her background, growing up with a brother who has cerebral palsy and considered himself disabled. Through his experience, she observed how he tried to access the world around him and the difficulty he had with technology. It was obvious to her that designers needed to build platforms that allow for better access to content and information.

Designers don’t decide who uses their platforms but should try to accommodate as much as possible, and be aware of how difficult this access can be for people, even those who might be using assistive or adaptive technologies to navigate. By being accessibility-focused, technology can bring the world to everyone, no matter their ability.

Understanding the Accessibility Needs of Users in UX

Many areas of disability need to be considered. One of the primary challenges with making the Internet available to all is knowing how and where to start to make digital products more accessible.

A first consideration is to not think about accessibility in terms of accommodating specific disabilities. Frequently, individuals may have multiple disabilities that interact with each other in a particular way. Instead, think about the needs of each user, what they want, and how they want to interact with what you’re building. That is far more important than identifying the specific disability or technology. Focus on what people need and how to accommodate them.

One way to do this is to think about four different perspectives on using technology and how to make it easier for people to access information.

(1) The first perspective concerns how people see written information which is more than visually accessing information. Not all people do this with their own eyes – they might have an equivalent experience of “seeing” something by listening to an audio version of the text.

(2) Second is how people hear recorded information. Having captions when a user can’t hear the audio content will be helpful in this area.

(3) Third is looking at how people find things on a website including how a user interacts with the content, whether with a voice interface, using a mouse, keyboard, or any number of adaptive technologies.

(4) Fourth is how to make information easy to understand.

These four perspectives accommodate a variety of ways that people understand not only the world but also individuals who may have cognitive disabilities or any kind of neurodiversity.

Breaking it down into those more simple perspectives makes it easier to think about when designing or researching a product rather than trying to cover all of the different possibilities in terms of disability.

Many researchers focus on one area at a time so this might feel counterintuitive. But if you’re testing with unknown users and people in the world, you may not know what they bring with them, as to abilities or disabilities.

Considering How Users Interact with Information

To navigate a combination of disabilities when creating designs, start with a focus, but then be flexible with individual needs that users may bring to the table. Much of that initial focus will be around a product itself or perhaps a particular area or component that you’re designing.

For example, if the focus is on text, consider more than just making it easy to read and understand. Be aware of how users interact with written text if they have difficulty with fine motor control, which can impact their ability to scroll, drag, or drop components. Users with these difficulties will need an alternative type of interaction for these actions.

It’s easier for the focal point to be on what you’re building. Equally important is how people will access that information. With accessibility in mind, you can explore and design different and better ways to build products.

How to Design for Edges Cases and Those in the Middle

Designing for the edge cases can bring in the middle by default. Focusing on improving a specific element of an experience, whether it’s text, audio, or video, ensures that it’s accessible to everyone.

When people first find out about accessibility, it may be tempting, for example, to adopt the mindset of creating an entirely different version of a product that is just for screen readers for those who are blind or have limited vision. But doing so implies making a choice for these users, assuming they need and want a different experience, and not considering that they may have their own way of interacting that you don’t necessarily understand yet.

When building better products for accessibility, it’s best to be as accommodating and flexible as possible and not rely on your assumptions. Strive to provide many ways for people to interact with what you’re building in the way they choose.

Pros and Cons of Accessibility Overlays

What is an accessibility overlay? If you browse the web as someone who has accessibility needs, it can best be described as an accessibility widget. It might be a circular button hovering around on a website as you’re scrolling that has a universal human icon on it. This widget is a plug-in that users can add to a website that creates an overlay to automatically make the entire product more accessible. You plug it in, and it does all the work. Because it is automatic, it may seem like an instant solution for all accessibility needs.

The problem is accessibility isn’t like that because people’s needs vary depending on the product. The accessibility is not done by a human, but rather by software that’s doing its best with the limited information it has access to. Your product will also have its own quirks and underlying code with which these widgets interact.

Another issue with an overlay is when users indicate that they want to use it, they are identifying themselves as having accessibility needs or as being disabled which can have privacy implications. Many products of this nature have third-party scripts that send data about the people browsing the sites to various served parties. For individuals who may not want to identify as disabled, this can have repercussions, affecting public services and other privacy concerns.

Often, these overlays don’t help users access website information. Designers who believe these overlays solve the problem may overlook crucial learning and understanding about accessibility and how they can make their product better. It’s best to view overlays as a temporary solution if there are specific needs that they can improve. But be sure they are solving those problems.

Accessibility is a Right, Not a Privilege

Developing technology with accessibility in mind opens up the world to more people than ever before. Access to products people use is a vital part of today’s infrastructure like the internet itself and how individuals participate in their social lives much of the time.

Included in this is access to public services, which is now primarily done through the web. But if these services are not accessible to some people because of a disability, that’s a problem. Such access is a human right, not a privilege for the few, that needs to be available to all.

Release of WCAG 2.2

WCAG is the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines and was introduced more than 25 years ago. It has gone through various iterations, with version 2.2 released in late 2023.

Version 2.1 was quite a departure from 2.0 in that it changed the approach of the guides to be less prescriptive about technology and more about how people use it since technology is changing all the time whereas the way people use it is changing less quickly. WCAG 2.2 has added more guidelines on specific use cases that come up in people’s experiences and areas that they might have difficulties with.

The new guidelines about dragging, for instance, is if you have an element that requires being dragged in your interface you must also provide a way of doing it that requires a single pointer interaction, by pointing and clicking with a mouse or using a keyboard.

Another example is making the clickable area for a link larger, even if the text is small. Doing so allows individuals who use a finger or a mouse or struggle for precise control to click that link as easily as anybody else. Data from behavioral analytics or heat maps can show if such areas need to be expanded. Therefore, if you have these components in what you’re building, make sure they are accessible to people who might struggle with fine motor skills.

The guide can seem overwhelming, but with this recent update, the language is easier to understand. Use it to get an overview of the needs people have as well as to understand accessibility in general.

But how about affecting change with stakeholders who may not understand the need for accessibility? It all depends on where you are in your organization. If you are a gatekeeper you could point out specific points that need to be more accessible.

But if you’re trying to do your best work where you are, inform yourself about potential accessibility issues around what you’re building and then work on ways to make improvements. You can still infuse things into your day-to-day work even if no one is telling you what you need to do.

WCAG Standard Levels

Most countries now have regulations around web accessibility based on WCAG guidelines. There are different level standards in WCAG: A, AA, or AAA, where AAA is the highest level of accessibility, and A is the lowest. Conformance at the highest level is also conformance at the lowest level. So if you base what you’re building around the AA standard then you’re usually in a good area. The updated 2.2 guidelines have checklists for all levels and are a great reference of how accessible your experience is, even if you’re not getting a professional audit done by a company.

See https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG22/ for more information.

Learning from Users to Understand Accessibility Needs

One of the best ways to know if your website is accessible to people with disabilities is to have it reviewed by people with these limitations. Companies such as Fable (makeitfable.com), Easy Surf (easysurf.ca – located in Canada), and Knowbility (knowbility.org) are all organizations built to do just that.

Discover best practices for remote testing with people who are using assistive and adaptive technologies. While you might focus on doing research with people who are using screen readers, they are often using other assistive and adaptive technologies.

As part of every test, consider asking about what technologies individuals use. There may be something you specifically want to test, but asking this question will inform you about other strategies people use to engage with information on the web. Self-reporting on the part of users can be extremely helpful in understanding how to meet their needs and is a great tool to take into any kind of form of accessibility. Listen to people and don’t make assumptions about their disabilities or how they access information. You may be the expert on research and design, but they are the experts on how they access what you create. Learn to trust what people tell you.

AI and Accessibility

AI has improved many aspects of accessibility including voice-activated interaction on a website to more accurate automatically-generated captions during a live Zoom call. Here again, be aware of privacy considerations. If someone uses their voice to communicate with a device, where else is that recording going without their knowledge? But overall, AI can be valuable in simple tasks and make navigation more accessible.

While AI may do a good job, don’t assume it does a great job. Automated captions, for instance, need to be checked by a human, particularly with technical topics or areas that have a lot of jargon associated with them. That’s where AI can fail. Also, be aware that AI tends to be biased towards English speakers and male voices and is better at generating captions when speakers have a North American accent.

A recent article proposed that AI could be used to generate an interface suitable to any particular user, specifically those with disabilities. Users could explain their disabilities and needs, and AI would generate a UI for them. While this would be wonderful if it worked, accuracy will be a huge issue especially if you want reliable information. Think about someone looking for information about a health issue, an area where getting it not quite right could have a disastrous effect. You don’t want AI guessing at it.

This goes back to the idea of having a specific interface for one person based on a specific disability instead of something that is accommodating to a wide variety of needs, allowing people to choose how they want to interact with it. For this to be effective, users would need to be singled out based on their disability not making it a viable solution. There are solutions that are working and those shouldn’t be thrown aside and replaced by the latest and greatest abilities of AI.

While AI is improving, believing it can support complete personalization for an individual is unrealistic right now. So what can be done until AI can deliver on that promise? Continue to create the best products with accessibility in mind that you can between now and whenever AI can provide better solutions.

What Disabilities Need to Be Addressed in Designing for Accessibility?

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) releases statistics each year on the prevalence of different areas of disability including mobility, self-care, cognitive disability, vision, and hearing. In the past, mobility has been the most prevalent disability in the United States. But in 2023 for the first time, cognitive disability, defined as serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, and making decisions, moved to the #1 spot. A hypothesis is that the inflammation from COVID-19 is negatively impacting the cognitive abilities of younger people.

Memory is an area people don’t think about in terms of accessibility, which brings to mind the importance of the humble breadcrumb, a reminder of where users have been and where they currently are on a website. Something as small as this makes information more accessible for people with memory issues. Other considerations are to incorporate shorter instructions and more repetition on writing tests.

Making instructions and navigation easy to understand in terms of text and labels will benefit those with cognitive difficulties as well as people who may not speak the language the interface is in. It also benefits people unfamiliar with terms, especially technical ones, long words, etc. Using plain and simple language is one of the easiest ways to accommodate the needs of a wide variety of people.

___________________________________________________________

1 https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html

Barriers to Accessibility

Another question to consider is if people avoid using products because they assume they’re not accessible. There’s no such thing as a hundred percent accessibility. There are too many varieties of needs that overlap in unexpected ways and often, those needs can be in conflict with each other.

Barriers pop up for everyone from time to time. such as when using a tricky interface and an unexpected bug appears. Most people know which tools work for them and will return to these products and services and become loyal to them. But they will also reject something if they have a bad experience or can’t use it.

If you believe that disabled people are not using your product, it might be because they can’t. People won’t buy your products If you make it impossible for them by putting up barriers.

When to Implement Accessibility Features

Across the development lifecycle, does it make sense to start at the low-fi prototype phase, do it at the high-fidelity phase, or wait until you’re in QA?

The answer is, you can start at any phase. However, the least expensive route is to start as early as possible, even before low-fi. When you’re considering what to build, and what your features and goals are, that’s the time to start thinking about accessibility because it will impact everything you do.

This is why Laura titled her book, Accessibility for Everyone, because it touches every discipline that will be working on a product or has a role within accessibility. Thinking about accessibility and how each stage could be affected is a mindset not unlike thinking about your business goals through all of the different life cycles of a product.

It will always be more expensive to change something after it is built. If you haven’t thought about accessibility early then you will need to write different code or design a slightly different way of interacting with it, and all of these things are expensive changes to make.

Accessibility and Short-term Disability

What about people who experience temporary disability? Is the design process similar for these individuals as for those with permanent accessibility needs?

This goes back to the idea of making something easy to see, hear, use, and understand. Someone might not have a disability related to motor skills, but if they broke their arm, they would not be able to use things in the way they could before. Suddenly they have an accessibility need. It’s not permanent, but no less inhibiting.

Laura shared her personal experience of suffering from severe RSI (Repetitive Strain Injury) in her arm and hand. “On the days when it’s awful, I can’t use a trackpad or a mouse so I have to use a keyboard. I’m suddenly thrown into a world of keyboard accessibility.” A quick test of a web product is whether you can browse it only using a keyboard because that’s the reality for many people with motor difficulties.

Impact of Design Systems on Accessibility

Should you incorporate accessibility into your design systems? That’s one of the coping strategies many organizations use to scale accessibility. Design systems can have a positive impact on providing a framework for accessibility in a digital experience.

Laura remembers talking to someone who had worked at Twitter who encouraged accessibility by designing a process that when something failed an automated accessibility test on the software side, it would result in an error which prevented further work until the error was resolved.

This isn’t just about showing people how to do things right but also about educating people on how to understand what the accessibility considerations are for this particular area of what is being built. Rather than accessibility being this amorphous big thing that’s difficult to understand and grasp, break it down into components and focus on the details around a smaller section, making it much easier to understand. You may be working on iterating one component, but as you bring that into the product, you’ve made it step by step a little bit more accessible.

Education is a big part of making accessibility a reality at an organization and benefits consistency and uniformity. Referring to cognitive or usability difficulties in general, you can learn how to design accessibility into one area and then apply what you learned to other areas to improve the overall product.

The Challenge of Incorporating Accessibility

Don’t be afraid of incorporating accessibility into your products. There are many ways in which accessibility can be intimidating to people. If you’re not disabled, you may feel intimidated by doing or saying the wrong thing or interacting in the wrong way. Do your best and take opportunities to speak to and respect what disabled people share about their experiences. If you can learn what is relevant to what you are working on, a little bit at a time, you will build up a breadth of knowledge very quickly. Your effort will provide breed greater creativity.

Along with the idea of incorporating accessibility is the question of whether accessibility research should have a distinct role or should all researchers learn how to do research alongside people with disabilities. It is evident that all researchers should include people with disabilities in their research, especially when trying to represent and understand the needs of a widespread audience.

A former student of Lija’s has the job title of “Accessibility UX researcher,” the only person she is aware of with that distinct title. Based on budget alone, most organizations won’t hire a few people whose primary responsibility is UX research, much less someone to address accessibility needs.

However, with AI becoming a bigger issue, organizations will need more people with that skill set to accommodate a broader range of disabilities. The idea of needing research specialists in this area is likely to grow in the future. These specialists can then guide the generalists to learn how to do best practices of incorporating accessibility in research.

. . .

Laura Kalbag is a British designer living in Ireland who has worked professionally in the tech industry for nearly 15 years. As someone interested in the entire user experience, she uses writing, speaking, and web development to support her work, with a particular focus on accessibility and privacy. Laura’s book, Accessibility For Everyone, was published by A Book Apart in 2017, and she has given over 100 talks at events worldwide.

Lija Hogan has specialized in usability and user needs research, design, and building UX teams. She teaches qualitative and quantitative UX research methods courses at the University of Michigan – Ann Arbor, on Coursera, and LinkedIn Learning. Lija’s current focus is inclusive research practice, as a Principal Customer Experience Consultant at UserTesting.

Group Pages

• Book Groups

– Accessibility for Everyone

• Do You Want to Be a UXR Consultant?

• Research Rumble

Session 1 – Research Democratization

Session 2 – Are Personas an Effective Tool?

Session 3 – How Important are Quant Skills to UX Research?

Session 4 – AI in UX Research

Session 5 – Do UX Researchers Need In-depth Domain Knowledge?

• How to Freelance

– Are You Ready to Freelance?

– Do You Need a Freelance Plan?

– How Do You Find Freelance Clients?

– Which Business Entity is Best for Freelancers?

– How to Manage a Freelance Business

– How to Start and Manage Your Freelance Business

– What is a Freelance UXR/UX Strategist?

– Can Your Employer Stop You From Freelancing?

• Leveling Up with UX Strategy

Session 1 – What is UX Strategy?

Session 2 – UX Strategy for Researchers

Session 3 – Working with Your UX Champions

• Quantitative UX Research Methods

Session 1 – When to Use Which Quantitative Methods

Session 2 – How to Use Statistical Tests in UX Research

Session 3 – Using Advanced Statistics in UX Research

• Transitioning to Freelance UX Research

Session 1 – Transitioning to Freelance

• Farewell Academia; Hello UXr

Session 1 – How to Create a UXr Portfolio

Session 2 – Creating UX Research Plans, Moderation Guides, and Screeners

Session 3 – Recruiting and Fielding UX Research Study Participants

Session 4 – Creating UX Analysis Guides and Portfolios

Session 5 – Portfolio Case Studies and LinkedIn Profiles, and Partnering with Recruiters

Session 6 – Framing Impact in UXr Portfolios and Resumes

Past Events

• How to Make Your Life as a Freelancer the Best it Can Be, August 12, 2021, via Zoom

– UX Research Freelance Work-Life Balance

• UXr Guild is Meeting UX Researchers in New York City, July 8, 2021, New York City

– How to Become a Freelance UX Researcher